Synchronization in Java

“Synchronization ensures that shared resources are accessed by only one thread at a time, preventing data inconsistency and race conditions.

-

In multithreading, multiple threads can access shared resources (like variables, objects, files).

-

Without synchronization → threads may interfere → causes race conditions.

-

Ensures one thread at a time executes a critical section.

-

Prevents data inconsistency.

-

Achieved using locks/monitors.

Can we use Volatile instead of Synchronization

Section titled “Can we use Volatile instead of Synchronization”“Volatile ensures visibility of changes across threads but doesn’t provide atomicity. It’s useful for simple flags but insufficient for compound operations.”

Race Conditions

Section titled “Race Conditions”“Race conditions are the most insidious bugs in concurrent programming - they’re intermittent, hard to reproduce, and often appear only under load.”

Example Without Synchronization

Section titled “Example Without Synchronization”class Counter { private int count = 0; public void increment() { count++; } public int getCount() { return count; }}Two threads calling increment() simultaneously can cause incorrect count output due to the non-atomic nature of the increment operation.

Example without Synchronization

Section titled “Example without Synchronization”class RaceConditionExample { private int counter = 0; public void increment() { counter++; } public int getCounter() { return counter; }

public static void main(String[] args) throws InterruptedException { RaceConditionExample obj = new RaceConditionExample(); Thread t1 = new Thread(() -> { for (int i = 0; i < 1000; i++) obj.increment(); }); Thread t2 = new Thread(() -> { for (int i = 0; i < 1000; i++) obj.increment(); }); t1.start(); t2.start(); t1.join(); t2.join(); System.out.println("Final: " + obj.getCounter()); // Often < 2000 }}✅ Expected = 2000

❌ Actual = some random number (due to race condition).

Important Note: Race conditions may not occur every time - their occurrence depends on how the operating system schedules thread execution on the CPU. This unpredictability makes them particularly dangerous.

Types of Synchronization Mechanisms

Section titled “Types of Synchronization Mechanisms”

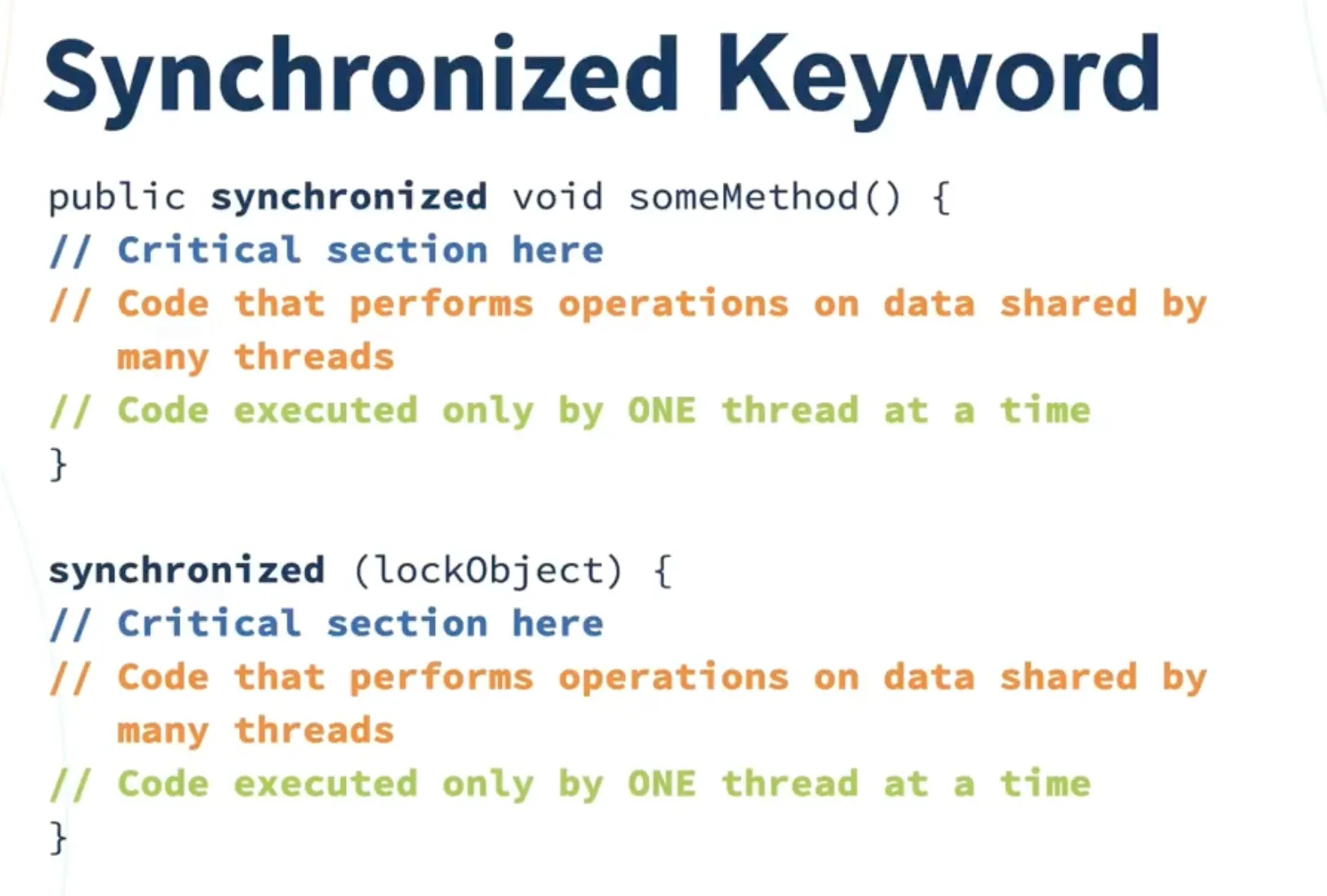

Synchronized Keyword

Section titled “Synchronized Keyword”“The synchronized keyword provides a simple and effective way to achieve thread safety, but it comes with performance overhead.”

Synchronized Method

Section titled “Synchronized Method”public synchronized void increment() { count++;}Synchronized Block

Section titled “Synchronized Block”public void increment() { synchronized(this) { count++; }}Synchronized Static Method

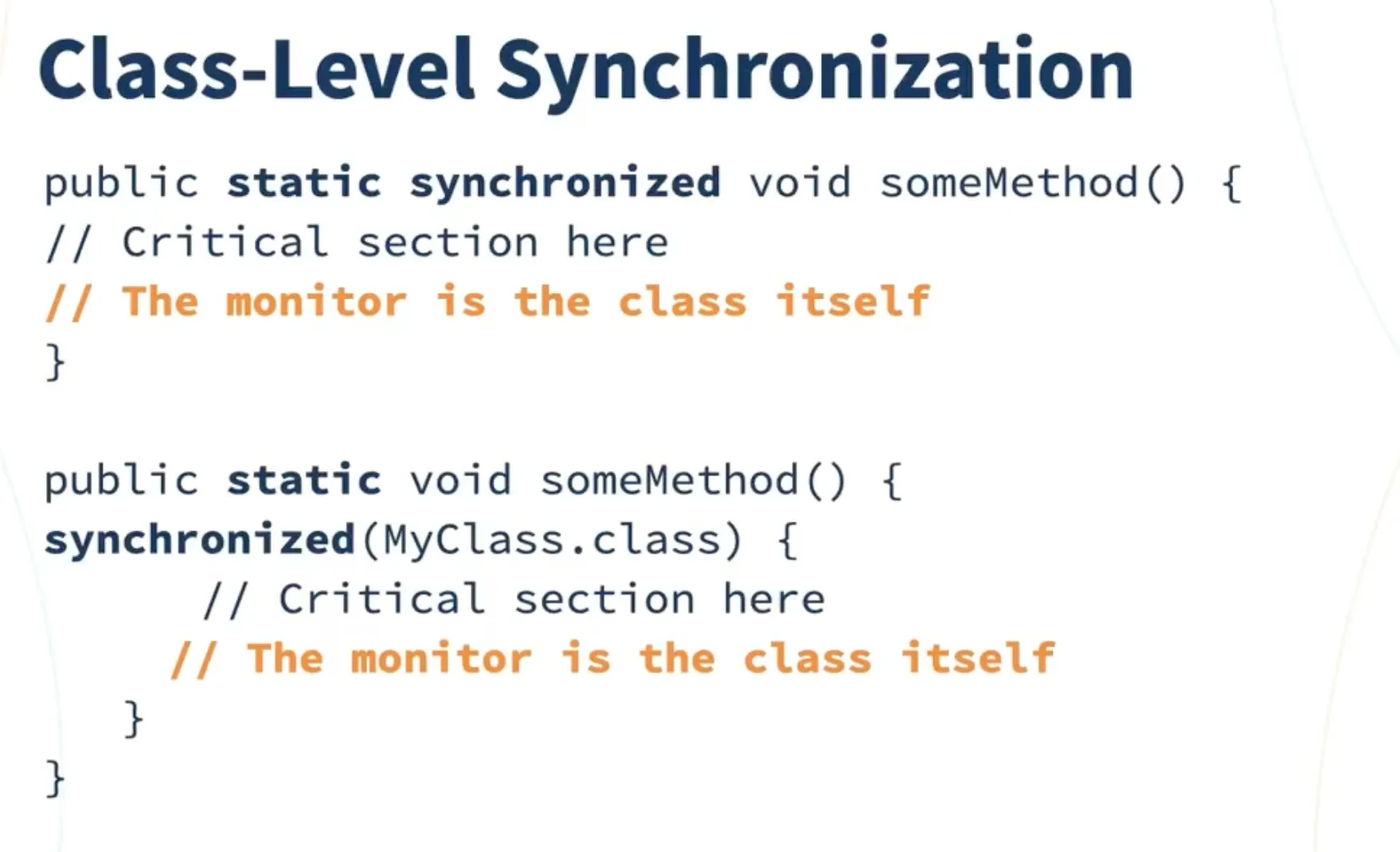

Section titled “Synchronized Static Method”public static synchronized void increment() { count++;}Class Level Synchronization (Static)

Section titled “Class Level Synchronization (Static)”- If method is static, it uses class-level lock (lock on

Classobject). -

- Only one thread per class can execute this method at a time.

Working Example with Synchronized

Section titled “Working Example with Synchronized”class Counter { private int count = 0; public synchronized void increment() { count++; } public int getCount() { return count; }}Reentrant Synchronization

Section titled “Reentrant Synchronization”-

A thread already holding a lock can acquire it again.

-

Example: One synchronized method calling another synchronized method of same object → no deadlock.

class ReentrantExample { public synchronized void method1() { System.out.println("Inside method1"); method2(); // re-enter same lock }

public synchronized void method2() { System.out.println("Inside method2"); }}Inter-thread Communication

Section titled “Inter-thread Communication”-

(

wait(),notify(),notifyAll()) -

Used to coordinate threads.

-

These must be used inside a synchronized block.

👉 Example (Producer-Consumer):

class SharedResource { private int data; private boolean available = false;

public synchronized void produce(int value) throws InterruptedException { while (available) wait(); // wait if data is already available data = value; available = true; System.out.println("Produced: " + value); notify(); // wake up consumer }

public synchronized int consume() throws InterruptedException { while (!available) wait(); // wait until data is available available = false; System.out.println("Consumed: " + data); notify(); // wake up producer return data; }}Deadlocks

Section titled “Deadlocks”- If multiple threads wait forever for each other’s lock → deadlock.

class DeadlockExample { public static void main(String[] args) { final String lock1 = "Lock1"; final String lock2 = "Lock2";

Thread t1 = new Thread(() -> { synchronized (lock1) { System.out.println("Thread 1: Holding lock1..."); try { Thread.sleep(100); } catch (Exception e) {} synchronized (lock2) { System.out.println("Thread 1: Holding lock1 & lock2..."); } } });

Thread t2 = new Thread(() -> { synchronized (lock2) { System.out.println("Thread 2: Holding lock2..."); try { Thread.sleep(100); } catch (Exception e) {} synchronized (lock1) { System.out.println("Thread 2: Holding lock2 & lock1..."); } } });

t1.start(); t2.start(); }}Best Practices

Section titled “Best Practices”-

Choose the Right Tool: Use

synchronizedfor simple cases,ReentrantLockfor advanced scenarios, andReadWriteLockfor read-heavy workloads. -

Minimize Lock Scope: Keep synchronized blocks as small as possible to reduce contention.

-

Avoid Nested Locks: Prevent deadlocks by acquiring locks in a consistent order.

-

Use Volatile Wisely: Only for simple flags and variables that don’t require atomicity.

-

Consider Performance: Profile your application to understand the impact of synchronization on performance.

Common Pitfalls

Section titled “Common Pitfalls”- Over-synchronization: Synchronizing methods that don’t need it

- Under-synchronization: Missing synchronization on shared data

- Lock Ordering: Inconsistent lock acquisition order leading to deadlocks

- Memory Visibility: Forgetting that

volatiledoesn’t provide atomicity

Remember: Synchronization is essential for thread safety, but it comes with performance costs. Always measure and profile to ensure you’re using the right approach for your specific use case.